As much as some deride celebrity journalism, the uncanny mystique of stars and our fascination with them isn't easily dismissed. Celebrity photographers, like Albert Watson, have also created iconic images that can nail an epoch and those who shape it. Back in 2012, Deirdre Kelly spoke to Watson for Critics at Large.

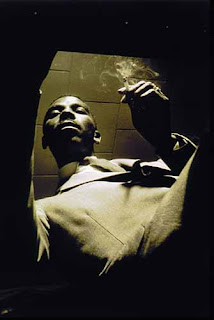

New York City-based celebrity photographer Albert Watson is a master of his profession. His images have appeared on more than a hundred Vogue covers and countless other publications from Rolling Stone to Time Magazine, many of them featuring now iconic portraits of rock stars, including David Bowie and Eric Clapton, in addition to Hollywood actors like jack Nicholson and Clint Eastwood and other notable high-profile personalities, including Steve Jobs, Mike Tyson, Kate Moss, Sade and Christy Turlington. Exhibited in art galleries and museums around the world, among them the Museum of Modern Art in Milan, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan, and the National Portrait Gallery in London, Watson recently made his Canadian debut at Toronto’s IZZY Gallery (106 Yorkville Ave; izzygallery.com) with a retrospective show called ARCHIVE, which closes on December 27. Aged 70 and with a career spanning 40 years, Watson is one of the few internationally acclaimed photographers still working exclusively in film, processing it himself in his dark room. All of his hand-processed images now hanging in Izzy Sulejmani’s gallery are for sale, enabling collectors as well as fans of Watson’s work to own something by one of the 20 most influential photographers of all time, according to Photo District News. “Photography is quick communication,” he told critic Deirdre Kelly during a recent visit to his New York City office lined with some of the images for which Watson is celebrated. “People easily get it.”

Here’s more of their conversation.

dk: These are wonderful digs you’ve got here in TriBeCa, close to the Hudson River and flooded with natural light. I am assuming this is where you work?

A Conversation with Photographer Albert Watson

| Jack Nicholson, from Albert Watson's Icons series, 1998 (All photos courtesy of the IZZY Gallery) |

New York City-based celebrity photographer Albert Watson is a master of his profession. His images have appeared on more than a hundred Vogue covers and countless other publications from Rolling Stone to Time Magazine, many of them featuring now iconic portraits of rock stars, including David Bowie and Eric Clapton, in addition to Hollywood actors like jack Nicholson and Clint Eastwood and other notable high-profile personalities, including Steve Jobs, Mike Tyson, Kate Moss, Sade and Christy Turlington. Exhibited in art galleries and museums around the world, among them the Museum of Modern Art in Milan, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan, and the National Portrait Gallery in London, Watson recently made his Canadian debut at Toronto’s IZZY Gallery (106 Yorkville Ave; izzygallery.com) with a retrospective show called ARCHIVE, which closes on December 27. Aged 70 and with a career spanning 40 years, Watson is one of the few internationally acclaimed photographers still working exclusively in film, processing it himself in his dark room. All of his hand-processed images now hanging in Izzy Sulejmani’s gallery are for sale, enabling collectors as well as fans of Watson’s work to own something by one of the 20 most influential photographers of all time, according to Photo District News. “Photography is quick communication,” he told critic Deirdre Kelly during a recent visit to his New York City office lined with some of the images for which Watson is celebrated. “People easily get it.”

Here’s more of their conversation.

|

| Photographer Albert Watson (Photo by Gloria Ro) |

dk: These are wonderful digs you’ve got here in TriBeCa, close to the Hudson River and flooded with natural light. I am assuming this is where you work?

aw: We don’t shoot here, no. I no longer have a studio of my own. We had a huge one in the West Village from 1987 to 2008, about 26,000 square feet. But I sold it to a hedge fund guy. Now, we don’t actually have a studio. We don’t need one. About 25 or 30 years ago, light in a space was fairly important. But nowadays you can replicate the light in a studio with technology. The business has changed, which is why we moved here. We’re now much more focused on supplying work for galleries and museums – fine art work and producing prints and making platinum prints. We make all our prints in the office and rent studios when we need them. Everyone told me that I would miss having my own studio. But I’ve spent my whole life working in Los Angeles, Berlin, Paris, Milan and other centres, including Toronto, and I’ve become quite used to photographing in other people’s studios. Where I work doesn’t have to be my own space.