One of Shlomo Schwartzberg's most passionate areas of interest is science fiction which is where his first posts began for Critics at Large shortly after the release of James Cameron's huge hit Avatar. Beginning with a critique of the film, it led Shlomo into a fascinating and expanded two-part exploration into why Hollywood rarely gets science fiction right. It's reprinted below in its entirety.

Can Hollywood ever get science fiction right? I ask this because I am baffled by the praise emanating from most critics towards James Cameron’s wretched 3D extravaganza Avatar. The story in this lengthy (2 hours, 40 minutes long) science fiction tale is simplicity (or simple mindedness) itself.

Can Hollywood ever get science fiction right? I ask this because I am baffled by the praise emanating from most critics towards James Cameron’s wretched 3D extravaganza Avatar. The story in this lengthy (2 hours, 40 minutes long) science fiction tale is simplicity (or simple mindedness) itself.

A cabal of scientists, mercenaries and corporate types are occupying the planet of Pandora and planning to get their hands on a precious mineral that they say Earth needs desperately. Our hero, Jake (Sam Worthington), a paraplegic Marine, is chosen to link up with one of the humanoid species, the Na’vi, who live on the planet, in order to get into its brain and attempt to communicate mankind’s 'peaceful' wishes to get the mineral even though it is found beneath the Na’vi’s holiest site. Needless to say, the Na’vi neither wants to move off the land nor allow the humans to drill for the mineral. But Jake, who can inhabit the virtual body of a Na’vi, and thus walk and run, begins to sympathize with the gentle humanoid species and slowly starts to turn against his military masters.

Amalgamating the worst parts of Terrence Malick’s loopy and New-Agey The New World and the black and white corporate / environmental world views of Naomi Klein / David Suzuki, Avatar is rife with bad dialogue (the Na’vi use unlikely words like ‘moron’ and the soldiers sound remarkably like present day grunts) and obvious symbolism – good natives, bad occupiers, all to the service of a tedious, cardboard cut-out story that barely leaves any emotional ripple in its wake. Oh, did I mention that it’s purportedly set in 2154, in a world where people speak exactly the same type of English as in our present, where the United States seems to be the only country in space? The technology, other than the avatar link ups between human and Na’vi, isn’t particularly novel, either. The soldiers wear watches, for God’s sake, something most 20somethings don’t even do anymore.

Perhaps the best way to analyze the deficiencies of Avatar, which doesn’t feel like it’s really set in the future, is to try a little experiment. Imagine society in hundred year increments, 1809, 1909, 2009, and think how much has changed in that 200 year span. How about in fifty year slices or even in twenty five year parts? In 1984,for example, CDs barely existed, the internet was hardly ubiquitous, flat screen TVs were a science fiction concept, DVDs didn’t exist and VHS was the order of the day. And these are the technological changes. I won’t even get into the social, philosophical and moral issues that have arisen since 1984, 17 years before 9/11. In that light, Avatar is simply wrongheaded. Oh, the portrait of Na’vi might seem interesting and original – after all, they’re blue skinned, ten feet tall, and have elongated limbs – but they’re actually more humanoid than alien, with colloquial language, basic emotions and actions that seem remarkably, well, human.

Now if Cameron, the public and the film critics, who have been praising his ‘bold’ vision, had read actually any of the recent imaginative science fiction novels that have portrayed aliens, or a compelling future, with utmost style and thought (Robert Charles Wilson’s Blind Lake, Theodore Judson’s Fitzpatrick’s War, Michael Swanwick’s Bones of the Earth, to name just three stellar books from some of the best writers in the field), they would have seen through the cant of Avatar. The film basically eschews any semblance of shading to its plot in favor of flashy pyrotechnics and expensive special effects. Yet, there’s a hint of something at the end of the film that suggests it needn’t have been cast as it was. An offhand reference to a ‘dying’ Earth seems to postulate that maybe, just maybe, the military / scientists have a legitimate reason for wanting to drill for unobtanium, the mineral at the centre of the film’s plot, and are thus much less villainous for coveting it. In that light, Avatar could have been a compelling tale of two cultures and peoples each with their own legitimate points of view, bumping up against each other, to tragic effect. But then Avatar would have to bring some nuance and complexity to the table instead of

what it is now.When I write about Hollywood not getting science fiction right, I should point out that I am mainly referring to the movies, which by necessity have to compress portraits of complex futures / societies into roughly two hour movies, though Avatar was longer than that. By comparison, successful SF series, i.e.: Battlestar Galactica, Babylon 5, Star Trek, etc., have the scope to delve into depictions of the future in more depth. That doesn’t mean that movies can’t do so, as well, but generally the people behind most SF films today aren’t making that attempt to deliver complexity and depth to the scenarios they offer us on screen.

So what makes a science fiction idea complex in the first place? Here's an interesting example from a comparative review I wrote a few years back for the Globe and Mail’s Books section. In the review I compared how two of Canada’s leading SF writers, Robert J. Sawyer and Robert Charles Wilson, in their novels wrote about societal attitudes towards smoking in the near future. In Sawyer’s book, Flashforward, which has just been turned into a successful ABC science fiction series, smoking in Canada and the U.S. has been made illegal in all public places, including outdoors. In The Chronoliths, by Robert Charles Wilson, which not incidentally is one of the finest time travel stories ever written in the field, smoking is actually illegal everywhere, but with the proviso that nicotine addicts get a one year grace period where they can get cigarettes via a doctor's prescription. After that, if they haven’t weaned themselves off the smokes, they’re breaking the law by indulging in that habit. The difference in how Sawyer and Wilson extrapolated the future of smoking is the difference between an obvious analysis of a continuing trend and a highly imaginative one. (Sawyer did predict an African – American president in Flashforward, which was written in 1999. But he was off by a few years.)

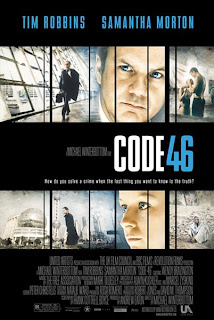

An operative cinematic comparison would be between Avatar’s future and the one depicted in Michael Winterbottom’s underrated and very fine, low key 2003 film Code 46. In its near future, people are matched up through genetic codes, hence the title of the film, which determine if they’re allowed to have a relationship. They are also, in a world run by a one world government, allowed to travel by permission only, and are required to carry ‘ papelles’, special travel permits when they do so. After William (Tim Robbins), a government investigator, is sent to Shanghai to look into a case of the manufacture of fake papelles, he begins an illegal relationship with Maria (Samantha Morton), the woman behind the fakes, with dire consequences for them both. There’s even more going on in the film but from its subtle use of futuristic slang, to the very idea of the papelles and the world’s geographic structure, cities for some, harsh desert for others deemed unfit for living in urban environments, there’s no doubt we’re in a future, recognizable to us in some ways but utterly alien in others.

I’d argue that Avatar’s future, by comparison, is only a surface future. There’s that throwaway reference to a dying Earth, the concept of linking up to an extraterrestrial species through an avatar and not much else to believably situate the movie in 2154. The characters in the film sound like us and act like us and the movie’s attitudes, towards its innocent alien natives, the environment, the gung ho military, its rapacious corporations etc. are right out of the propaganda handbook of Michael Moore. But if mankind or humankind is going to go into space and eventually encounter aliens, a military presence will be essential, to help protect humans when they build their habitats on other planets, and to repel those who might attack us. Similarly, governments will likely not have monies available to fund space operations, especially ones that take years to come to fruition, so corporations will likely be tapped for those funds. Thus, both soldiers and CEOs will be at worst necessary evils but more likely will be seen as saviours of mankind as we propel ourselves into other worlds and go where no man has gone before. (Sorry, I couldn’t resist the Star Trek reference.)

You won’t, however, find any of those smart and challenging points of view in Avatar, as James Cameron prefers instead to pander to the worst, left wing, liberal prejudices of his Hollywood confreres and thus offers his potential audience, propaganda of the dullest, flattest sort. His movie isn’t even good agit – prop. Those film critics, who have unfathomably fallen for his okey doke (as writer Harlan Ellison, who successfully sued Cameron for plagiarizing his work in The Terminator, would put it), either acknowledge but excuse the movie’s flaws because they buy into his point of view (Maclean’s’s Brian D. Johnson, for one) or are so dazzled by the film's 3-D special effects, that they don’t even notice them. The movie does look great and the 3-D is as unobtrusive as can be but so what? I would expect the movie, which is reportedly budgeted at between $200 – 300 million, to look stupendous, considering its obscene cost. But an expensive Hollywood film with great FX is about as unusual as a processed food dish with too much salt. One wants and should expect more in a science fiction movie.

Unfortunately, Avatar, the lame X- Men movies, the inferior Terminator sequels, M, Night Shyamalan’sSigns and The Village and Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds and Minority Report, to name just a few SF films of late, are the unimaginative Hollywood norm and the smart flicks, from outside Hollywood (Code 46) or within (J J. Abram’s Star Trek, Spielberg’s AI: Artificial Intelligence) are the exceptions to the rule. Hollywood, which knows nothing of the rich genre that is written science fiction, or even recalls the clever SF films of the 50s, such as The Incredible Shrinking Man and The Day The Earth Stood Still, prefers not to get it right. Alas, the incredibly successful Avatar, which seems to be on its way to becoming the highest grossing movie of all time, only ensures that in the future we will get more of the mediocre same.

The Trouble With Avatar

Can Hollywood ever get science fiction right? I ask this because I am baffled by the praise emanating from most critics towards James Cameron’s wretched 3D extravaganza Avatar. The story in this lengthy (2 hours, 40 minutes long) science fiction tale is simplicity (or simple mindedness) itself.

Can Hollywood ever get science fiction right? I ask this because I am baffled by the praise emanating from most critics towards James Cameron’s wretched 3D extravaganza Avatar. The story in this lengthy (2 hours, 40 minutes long) science fiction tale is simplicity (or simple mindedness) itself.A cabal of scientists, mercenaries and corporate types are occupying the planet of Pandora and planning to get their hands on a precious mineral that they say Earth needs desperately. Our hero, Jake (Sam Worthington), a paraplegic Marine, is chosen to link up with one of the humanoid species, the Na’vi, who live on the planet, in order to get into its brain and attempt to communicate mankind’s 'peaceful' wishes to get the mineral even though it is found beneath the Na’vi’s holiest site. Needless to say, the Na’vi neither wants to move off the land nor allow the humans to drill for the mineral. But Jake, who can inhabit the virtual body of a Na’vi, and thus walk and run, begins to sympathize with the gentle humanoid species and slowly starts to turn against his military masters.

Amalgamating the worst parts of Terrence Malick’s loopy and New-Agey The New World and the black and white corporate / environmental world views of Naomi Klein / David Suzuki, Avatar is rife with bad dialogue (the Na’vi use unlikely words like ‘moron’ and the soldiers sound remarkably like present day grunts) and obvious symbolism – good natives, bad occupiers, all to the service of a tedious, cardboard cut-out story that barely leaves any emotional ripple in its wake. Oh, did I mention that it’s purportedly set in 2154, in a world where people speak exactly the same type of English as in our present, where the United States seems to be the only country in space? The technology, other than the avatar link ups between human and Na’vi, isn’t particularly novel, either. The soldiers wear watches, for God’s sake, something most 20somethings don’t even do anymore.

Perhaps the best way to analyze the deficiencies of Avatar, which doesn’t feel like it’s really set in the future, is to try a little experiment. Imagine society in hundred year increments, 1809, 1909, 2009, and think how much has changed in that 200 year span. How about in fifty year slices or even in twenty five year parts? In 1984,for example, CDs barely existed, the internet was hardly ubiquitous, flat screen TVs were a science fiction concept, DVDs didn’t exist and VHS was the order of the day. And these are the technological changes. I won’t even get into the social, philosophical and moral issues that have arisen since 1984, 17 years before 9/11. In that light, Avatar is simply wrongheaded. Oh, the portrait of Na’vi might seem interesting and original – after all, they’re blue skinned, ten feet tall, and have elongated limbs – but they’re actually more humanoid than alien, with colloquial language, basic emotions and actions that seem remarkably, well, human.

Now if Cameron, the public and the film critics, who have been praising his ‘bold’ vision, had read actually any of the recent imaginative science fiction novels that have portrayed aliens, or a compelling future, with utmost style and thought (Robert Charles Wilson’s Blind Lake, Theodore Judson’s Fitzpatrick’s War, Michael Swanwick’s Bones of the Earth, to name just three stellar books from some of the best writers in the field), they would have seen through the cant of Avatar. The film basically eschews any semblance of shading to its plot in favor of flashy pyrotechnics and expensive special effects. Yet, there’s a hint of something at the end of the film that suggests it needn’t have been cast as it was. An offhand reference to a ‘dying’ Earth seems to postulate that maybe, just maybe, the military / scientists have a legitimate reason for wanting to drill for unobtanium, the mineral at the centre of the film’s plot, and are thus much less villainous for coveting it. In that light, Avatar could have been a compelling tale of two cultures and peoples each with their own legitimate points of view, bumping up against each other, to tragic effect. But then Avatar would have to bring some nuance and complexity to the table instead of

what it is now.

So what makes a science fiction idea complex in the first place? Here's an interesting example from a comparative review I wrote a few years back for the Globe and Mail’s Books section. In the review I compared how two of Canada’s leading SF writers, Robert J. Sawyer and Robert Charles Wilson, in their novels wrote about societal attitudes towards smoking in the near future. In Sawyer’s book, Flashforward, which has just been turned into a successful ABC science fiction series, smoking in Canada and the U.S. has been made illegal in all public places, including outdoors. In The Chronoliths, by Robert Charles Wilson, which not incidentally is one of the finest time travel stories ever written in the field, smoking is actually illegal everywhere, but with the proviso that nicotine addicts get a one year grace period where they can get cigarettes via a doctor's prescription. After that, if they haven’t weaned themselves off the smokes, they’re breaking the law by indulging in that habit. The difference in how Sawyer and Wilson extrapolated the future of smoking is the difference between an obvious analysis of a continuing trend and a highly imaginative one. (Sawyer did predict an African – American president in Flashforward, which was written in 1999. But he was off by a few years.)

An operative cinematic comparison would be between Avatar’s future and the one depicted in Michael Winterbottom’s underrated and very fine, low key 2003 film Code 46. In its near future, people are matched up through genetic codes, hence the title of the film, which determine if they’re allowed to have a relationship. They are also, in a world run by a one world government, allowed to travel by permission only, and are required to carry ‘ papelles’, special travel permits when they do so. After William (Tim Robbins), a government investigator, is sent to Shanghai to look into a case of the manufacture of fake papelles, he begins an illegal relationship with Maria (Samantha Morton), the woman behind the fakes, with dire consequences for them both. There’s even more going on in the film but from its subtle use of futuristic slang, to the very idea of the papelles and the world’s geographic structure, cities for some, harsh desert for others deemed unfit for living in urban environments, there’s no doubt we’re in a future, recognizable to us in some ways but utterly alien in others.

I’d argue that Avatar’s future, by comparison, is only a surface future. There’s that throwaway reference to a dying Earth, the concept of linking up to an extraterrestrial species through an avatar and not much else to believably situate the movie in 2154. The characters in the film sound like us and act like us and the movie’s attitudes, towards its innocent alien natives, the environment, the gung ho military, its rapacious corporations etc. are right out of the propaganda handbook of Michael Moore. But if mankind or humankind is going to go into space and eventually encounter aliens, a military presence will be essential, to help protect humans when they build their habitats on other planets, and to repel those who might attack us. Similarly, governments will likely not have monies available to fund space operations, especially ones that take years to come to fruition, so corporations will likely be tapped for those funds. Thus, both soldiers and CEOs will be at worst necessary evils but more likely will be seen as saviours of mankind as we propel ourselves into other worlds and go where no man has gone before. (Sorry, I couldn’t resist the Star Trek reference.)

You won’t, however, find any of those smart and challenging points of view in Avatar, as James Cameron prefers instead to pander to the worst, left wing, liberal prejudices of his Hollywood confreres and thus offers his potential audience, propaganda of the dullest, flattest sort. His movie isn’t even good agit – prop. Those film critics, who have unfathomably fallen for his okey doke (as writer Harlan Ellison, who successfully sued Cameron for plagiarizing his work in The Terminator, would put it), either acknowledge but excuse the movie’s flaws because they buy into his point of view (Maclean’s’s Brian D. Johnson, for one) or are so dazzled by the film's 3-D special effects, that they don’t even notice them. The movie does look great and the 3-D is as unobtrusive as can be but so what? I would expect the movie, which is reportedly budgeted at between $200 – 300 million, to look stupendous, considering its obscene cost. But an expensive Hollywood film with great FX is about as unusual as a processed food dish with too much salt. One wants and should expect more in a science fiction movie.

Unfortunately, Avatar, the lame X- Men movies, the inferior Terminator sequels, M, Night Shyamalan’sSigns and The Village and Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds and Minority Report, to name just a few SF films of late, are the unimaginative Hollywood norm and the smart flicks, from outside Hollywood (Code 46) or within (J J. Abram’s Star Trek, Spielberg’s AI: Artificial Intelligence) are the exceptions to the rule. Hollywood, which knows nothing of the rich genre that is written science fiction, or even recalls the clever SF films of the 50s, such as The Incredible Shrinking Man and The Day The Earth Stood Still, prefers not to get it right. Alas, the incredibly successful Avatar, which seems to be on its way to becoming the highest grossing movie of all time, only ensures that in the future we will get more of the mediocre same.

No comments:

Post a Comment