This past year, the late film critic Pauline Kael, who died in 2001, became a subject of great debate due to a biography by Brian Kellow (which is perhaps the first major biography of a film critic) and a new collection of previously published reviews. The debate itself seem curiously centered around Kael's continued relevance as a film critic, something unassailable to Steve Vineberg who knew her and Kevin Courrier who interviewed her back in 1983.

Reflections on Pauline Kael

The simultaneous publication of Brian Kellow’s biography Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark (Viking, 2011) and The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael, a Library of America anthology of her movie criticism edited by Sanford Schwartz, restores Pauline Kael's status as the most important film reviewer in the history of the medium. All thirteen of her books, including the last cross-section, For Keeps, which she assembled herself in 1994, are out of print; movies no longer generate the excitement, the intellectual debate and generational ownership, that they did while Kael held her post atThe New Yorker – especially in the first decade (1967-1976) of her tenure, when the “Current Cinema” column passed back and forth at six-month intervals between her and Penelope Gilliatt. (Kael got it to herself when she returned to the magazine in 1980 after a brief stint in Hollywood; in the last few years before she retired in 1991, she shared it with Terrence Rafferty.) Reading Kellow’s book and dipping into the Library of America volume brings back some of the feeling of movie-going during the Vietnam era, when Hollywood was undergoing a renaissance no one could have anticipated and the latest imports from Europe enhanced the sense Kael had – and communicated eloquently to her readers – that we were living in a charmed period for the medium. Kael always acknowledged her luck at beginning to write regularly about movies (her appointment at The New Yorker, at the age of 48, was her first extended paying gig) just at the moment when old Hollywood was collapsing and younger, hip directors and screenwriters who sparked a connection with the new, counter-cultural audience were slipping into the crevasses. We were lucky because she understood the cultural significance of what she saw up on the screen and had the critical astuteness that allowed her to evaluate its quality.

Kael brought a combination of common sense, sensibility, a love and understanding of acting and a dense and detailed comprehension of all the arts to her reviewing. And her opinions were blessedly unshackled by orthodoxy on the one hand (the reverence for entrenched filmmakers or prestige film making or Academy Award winners; the confusion of moralizing and solemnity with profundity) and theory on the other. Her prose was forthright, colloquial and rhythmic; she was a gifted and completely original stylist. She got people thinking about movies in new ways and inevitably she exerted a powerful influence on the generation of critics that followed her, those who (like myself) were in high school or college when we, too, first encountered Bonnie and Clyde and McCabe and Mrs. Miller and The Godfather. That influence stirred up controversy, one of several in Kael’s career. God knows she infuriated people. Unsurprisingly, directors and producers who felt slapped down in some of her reviews disliked her, and studio publicists would punish her for bad notices by cutting her from screenings. But though she had devoted fans both inside and outside the business, the passion of her conviction, the confidence with which she rendered her opinions and the strength of her arguments often unsettled her readers, especially when the movies she targeted were the ones they loved. I don’t know whether Kael was the first movie critic to discover how venomous moviegoers can become when confronted with carefully worked-through arguments against a beloved film, but some of her judgments elicited violent, menacing letters. And she had her enemies among her fellow critics – like Andrew Sarris, long associated with The Village Voice, whom she incited when, in one of her earliest (pre-New Yorker) pieces, she attacked his auteurist approach to writing about movies; Renata Adler, a peripatetic reviewer who used the publication of one of Kael’s collections, When the Lights Go Down, in 1980 to launch a lengthy and hysterical attack on her writing in The New York Review of Books; Stuart Byron, also at theVoice, who, inflating flimsy evidence, branded her a homophobe.

I knew Kael well for the last seventeen years of her life. My hero among movie critics during my college years, she became a mentor and then a close friend. Reading Kellow’s book (he interviewed me for it) and thinking about reviewing it have been, I confess, odd experiences. Anyone who knew Kael, in a sense, knows too much to read a biography of her with the calm that arises from emotional distance. But my feelings about her work didn’t alter when we became friends. She knocked me out when I read her on Barbra Streisand’s performance in Funny Girl in my first semester at college in 1968; she knocked me out again when, at the end of my third year as a college professor, I read her review of Brian De Palma’s Vietnam picture Casualties of War. And this isn’t the first time I’ve written about her: I published an essay on her work called “Critical Fervor” in The Threepenny Review a year after she retired from The New Yorker, and The Boston Phoenix ran my obituary on her in September 2001. The dual publication of Kellow’s book and the Library of America volume has rekindled some of the old controversies and has brought out of the woodwork a variety of people who – like many when she was alive, and some after her death – have evidently been champing at the bit to get in a few potshots. Frank Rich, for example, writing in The New York Times Book Review, claims to have been an admirer yet manages to re-imagine Kellow’s scrupulously fair-minded account of her post-Hollywood years at The New Yorker as retribution for her many sins (he includes the notoriously mean-spirited Adler piece in this accounting, introducing it with the phrase “Someone had to cry foul,” as if Adler were the voice of justice speaking out at last). He even accuses Kael of hypocrisy because, having mocked Dwight Macdonald for comparing Alain Resnais’s art-house darling Hiroshima, Mon Amour to Joyce and Stravinsky, she evokes Ulysses and Stravinsky’s Le sacre du printemps in her reviews of, respectively, Robert Altman’s Nashville and Bernardo Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris. It seems pretty clear that Kael’s complaint about Macdonald’s praise of the Resnais picture was that it didn’t deserve the comparison, not that it is intellectually reprehensible to allude to Joyce in a discussion about a movie.

A Life in the Dark is a conscientious piece of work. Kellow is an excellent writer and evidently a tireless researcher. The first hundred pages uncovers a vivid story about Kael’s northern-California upbringing (to Polish-Jewish émigrés who settled in a Petaluma chicken-farming community and then, when Isaac Kael lost his money in the late twenties, in San Francisco), her life among bohemians in both the Bay Area and New York in the 1940s, her scrambling among a wide range of jobs in the late forties and the fifties to support herself and her daughter (whose father, the documentary filmmaker James Broughton, threw Kael out when she told him she was pregnant), and her days managing the Berkeley Guild, a revival house, and reading her movie reviews gratis on the KPFA radio station in San Francisco. The letters he quotes reveal her spiky, jocular, anti-conventional personality, already apparently fully formed in her twenties, and occasionally an observation that prefigures her focus on disparate elements and moments in all sorts of movies once she began writing about them. In a 1941 letter to her friend Violet Rosenberg, she urges her to see So Ends Our Night for “the most beautiful shot of Frances Dee, standing in a European marketplace.”

Most of the book, of course, centers on her criticism. She writes her famous review of Bonnie and Clyde for The New Yorker on page 100, less than a third of the way in, and its editor-in-chief, William Shawn, hires her as a regular reviewer four pages later. And that makes her story, as Kellow acknowledges, a somewhat bizarre one for a biography, because at that point she stops having adventures and settles into the position she will hold, except for the sabbatical in Hollywood, for nearly a quarter of a century. She doesn’t live the kind of life that a typical biography thrives on; aside from her complicated relationship with her daughter Gina James, which Kellow can only report on indirectly through random observations by her friends, since Gina declined to be interviewed for the book, there isn’t anything for him to write about besides her writing and the controversies it sometimes provokes. He makes a concerted effort to do so squarely, and his reportage is objective, but it doesn’t contain a great deal of substance. Kellow is intelligent but he isn’t a movie critic, so he doesn’t have much of his own to add to his re-enactments of the high and low points of each new season. And when he does throw in his own opinion it’s unhelpful and sometimes baffling, as in his head-scratching comments about her championing of De Palma’s movies and his branding as “peculiar” her claim, in her second collection of published pieces, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, that Katharine Hepburn is “probably the greatest actress of the sound era.” (Surely that’s not a controversial pronouncement, especially considering the context is Hepburn’s staggering performance in Long Day’s Journey into Night.) It wouldn’t be a problem that he sometimes takes issue with something in one of her reviews – it doesn’t arise very often – if those flaws he spots didn’t always seem to be based on a misreading. For instance, he balks at “Notes on the Nihilist Poetry of Sam Peckinpah,” an anomalous piece of analysis (and I would say one of her most amazing) that sees the conflicts in Peckinpah’s movies as a symbolic representation of the way he perceived his own struggles against producers and studio heads. Kellow calls the piece “a lengthy mash note” that “all but turn[s] Peckinpah [one of her favorite filmmakers] into a Christlike figure.” He misses the crucial distinction that it’s Peckinpah, not she, who’s presenting himself in that light: “Peckinpah is surely one of the most histrionic men who have ever lived: his movies (and his life, by now) are all gesture”; “Peckinpah has become wryly sentimental about his own cynicism”; “going so far into his own hostile, edgily funny myth – in being the maimed victim who rises to smite his enemies”; and so forth.

Kellow’s misreading gets in the way when he tries to psychoanalyze Kael through her reviews – a temptation that probably no biographer of a writer could resist, but perhaps particularly misguided in this case, since Kael was so nakedly autobiographical in her writing. (It’s unlikely that anyone who confesses that she saw Vittorio De Sica’s devastating Shoeshine after a terrible, unresolvable quarrel with her boyfriend needs to have her judgments examined for hidden motives.) A glaring instance is his discussion of her review of Claude Lanzmann’s 1985 Holocaust documentary Shoah, a movie almost everyone else praised to the skies and Kael hated. (Though she had legendary fights with Shawn over her copy, it was the only time she submitted a review that he refused at first to publish at all.) Kellow pointedly prefaces this section with a paragraph on her “unsentimental attitude toward her Jewish background” and a story about her balking at a dinner party when another Jewish guest refused to eat ham and ends it with the statement, “[I]t was difficult to shake off the feeling that her thinking was influenced by other factors, of which she was only partly conscious.” But he takes the sentence that provokes this response – “If you were to set [Lanzmann] loose, he could probably find anti-Semitism anywhere” – out of context. “It was a stunning lapse of judgment,” Kellow writes, “considering that Lanzmann was looking for anti-Semitism in the most obvious of places – the death camps.” Well, no: Kael is referring not to the Nazis but to his indictment of the Polish Gentiles whom he persists in depicting as callous to the fates of the Jews thrown in the death vans. I haven’t seen the film since its release (I wrote one of the few other dissenting reviews of it), but I remember that the movie clearly conveyed Lanzmann’s anger at Polish peasants who gestured at Jews on the vans by drawing their hands across their throats. He’s sure those gestures must have been mocking; given the evidence I think it’s just as likely they were trying to warn the victims. (A friend who is fluent in Polish told me after seeing the film that Lanzmann mistranslates some of the testimony of the Poles he interviews to make them sound more insensitive.)

I think that’s a failure of interpretation on Kellow’s part, not a failure of intention, but it’s not the only time in the book when his attempt to be balanced is hamstrung by what he doesn’t know or doesn’t see or doesn’t understand. Take “Raising Kane,” her famous essay on Citizen Kane, which raised the hackles of Orson Welles enthusiasts like the director Peter Bogdanovich because it aimed to restore the screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz’s role in the film’s triumph after Welles had spent three decades claiming, with increasing vociferousness, that he was the main writer. Kellow reads the essay as a crusade against the auteurist theory she’d slammed Sarris for a decade earlier in the article “Circles and Squares,” and it’s certainly a confirmation of her belief that movies are the work of too many hands to be purely the reflection of a single penetrating vision. Yet he also protests that when she “speculated that Gregg Toland, Kane’s cinematographer, had played a previously unsuspected role in the picture’s overall look . . . point[ing] to an obscure thriller from 1935 called Mad Love” that Toland shot, that “she had no real evidence for [this] theor[y]” and “the part about Mad Love was basically the same sort of movie detective work she had accused the auteurists of peddling.” Well, no: actually she comes up with pretty strong visual evidence (look at Mad Love) and identifying Toland’s contribution as consistent with his previous work is no more “auteurist” than saying that you can spot the origins of Brando’s performance in Last Tango in Paris in his early, groundbreaking work in movies like A Streetcar Named Desire and On the Waterfront.

Kellow handles some of the controversies in Kael’s career more with a surer hand than others – I think he’s particularly good in both explicating and diffusing the charge that she was a homophobe. At other times, though, the emphasis his text places on the testimony of some of his interviewees and the absence of a strong counterargument allow their point of view to stand, even when it’s suspect. The book is dotted with comments by detractors who claim that once Kael took exception to a director he was dead meat as far as she was concerned, that she always put forward her pet directors, that she often overrated them, and that ironically her favoritism was just as blind as the devotion of the auteurists totheir chosen directors. But Kael’s objection to the auteur theory was that it elevated mediocre work by praising it for illuminating elements of a director’s style and for reflexively conferring greatness on any picture, no matter how drab, that carried a credit to one of certain directors. She never denied that some directors – Griffith, Renoir, De Sica, Satyajit Ray, Godard – were masters, and she never genuflected before a movie just because she’d loved the director’s previous work. She adored Altman’s work but she hated every movie he turned out between Nashville in 1975 and Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean in 1982. She adored Peckinpah’s work but not Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid or The Getaway, De Palma’s but not Obsession, Scarface, Body Double or The Bonfire of the Vanities.

Generalizations simply don’t work on Kael, because one of her great qualities as a critic was that she weighed every movie on its own merits and could see it in all its aspects – a virtue that links her to James Agee, the signal movie critic of the forties, whom she much admired. So when Kellow argues that she thought moviemakers did their best work when they were young and energetic, you think, Well, except for John Huston, Kon Ichikawa and Luis Buñuel, and how about De Sica’s return to greatness with The Garden of the Finzi-Continis? And when he puts forward the theory that she had a Magellan complex, that she found it easier to get behind filmmakers she’d discovered, you think, Well, except for Renoir and Preston Sturges and the German Expressionists. She was notoriously – and to many, not just publicists, exasperatingly – unpredictable because she didn’t believe the movies themselves could be predicted. So while she was unkind to David Lean’s epics, she loved several of his early, smaller pictures (Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, Hobson’s Choice) and she shocked everyone by giving his last, A Passage to India, a rave. She bemoaned the big studios’ chasing after the success of The Sound of Music (a picture she loathed) by turning out musical behemoths in the late sixties, but she sometimes found things to praise in them – the early scenes in Coppola’s Finian’s Rainbow, the performances in Goodbye, Mr. Chips – and she always acknowledged the times when old-style Hollywood filmmaking worked, as it did in Fiddler on the Roof. She found all of Ingmar Bergman’s work between the late fifties and the late sixties tiresome and overrated but she wrote rapturously about his apocalyptic war film Shame in 1968. She could excoriate a movie but find something marvelous hiding in one of its corners – Anthony Perkins’s performance in Play It as It Lays or Austin Pendleteon’s in Billy Wilder’s vulgarized remake of The Front Page.

Kael was often taken to task for her personal relationships with directors whose work she loved. Kellow shows that those friendships didn’t prevent her from writing disparagingly about one of their movies (though it sometimes cost her the friendship). So it’s puzzling when he suggests that had Robert Getchell – who’d sent her his screenplay Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore before it ended up in Martin Scorsese’s hands – given it to Altman, as she recommended, she might have been in some kind of professional quandary when the picture came out, or when he criticizes her for not admitting, in her rave review of David Lynch’s The Elephant Man, that she promoted the screenplay during her time in Hollywood. Presumably she promoted it because she liked it, then praised it when Lynch shot it because she still liked it. Perhaps most of us couldn’t look at a friend’s work with clear eyes, but Kael could; that’s why, as many of the young writers she encouraged attest, she was such an invaluable editor. Her relationships with the critics she mentored – who acquired the unfortunate nickname the Paulettes – is another bone of contention, and since I was one of them I find this controversy rather weird to discuss. Mostly Kellow takes a liberal perspective on it, essentially saying that some of those relationships turned out better than others (true enough) and that some of her acolytes – his chosen word – behaved more admirably than others (equally true). He’s careful to point out that though she liked her friends to agree with her on movies, she also courted people who fought with her and she found younger writers who imitated her creepy. He doesn’t give credence to the persistent rumor that she attempted to orchestrate others’ opinions or galvanize them for purposes of voting in the New York Film Critics’ Circle, to which she belonged, or the National Society of Film Critics, of which she was one of the founding members. But then, close to the end of the book, in a reference to an article by the Village Voice critic Georgia Brown that accuses her without evidence of doing just that, Kellow writes, “[S]he strongly suggested that Pauline was guilty of . . . organizing her acolytes in a voting bloc – a point she might have been able to prove had she done her homework . . .”

This disturbing hint comes at the end of a chapter, which gives it considerable weight, even though it seems to come out of the blue and Kellow never says what sort of homework might have confirmed Brown’s accusation. Did he do it himself and then decide not to share it with us? The previous chapter ends with a quote from Owen Gleiberman, who has been for many years the film critic at Entertainment Weekly, in which he claims that while he was friendly with Kael he applied for admission to the National Society of Film Critics and was initially turned down. When he asked her to tell him why, she gave him an answer that he knew immediately wasn’t the truth so he decided to break with her because “I realized that she would lie to her critic acolytes in order to keep them in line.” But nothing in the story suggests how lying to Gleiberman would keep him in line; the story is melodramatic and implausible and seems to promote his presentation of himself as intuitive and perceptive. You’d think Kellow would be smart enough not to quote this sort of nonsense, at least not without some editorial commentary. Instead he adds, “Gleiberman always considered himself the truest of all the Paulettes because he had realized that he had to be himself. ‘To be true to what Pauline taught us,’ he said, ‘you had to break with her.’ ” Gleiberman paints himself as a hero, a man of singular integrity, and by giving him the final word on the subject and refusing to challenge it Kellow lets this self-promotion stand.

Perhaps it’s unfair to expect Kellow to do for Kael’s writing what, say, Sanford Schwartz does in his fine introduction to The Age of Movies, because Schwartz isn’t a biographer and Kellow isn’t a critic. But how do you write the life of a movie critic if you don’t have much to offer on the subject of movies? I realize that it’s unfair to single out all the problems I had with A Life in the Dark and discuss them at such length because it gives the book’s considerable virtues short shrift. But the lacunae in Kellow’s book seem to me to be precisely in the areas where Kael’s accomplishments are always underappreciated and where the traditional complaints against her need to be placed in a context that he doesn’t seem equipped to provide. The book is fair, if weighing everyone’s opinion is fair, but it isn’t always accurate. Schwartz argues that Kael’s body of work “sometimes has the impact of a single long, indirect, and utterly original kind of autobiography” and I suppose that, in the end, that’s the biography of Pauline Kael that I prefer.

Kael brought a combination of common sense, sensibility, a love and understanding of acting and a dense and detailed comprehension of all the arts to her reviewing. And her opinions were blessedly unshackled by orthodoxy on the one hand (the reverence for entrenched filmmakers or prestige film making or Academy Award winners; the confusion of moralizing and solemnity with profundity) and theory on the other. Her prose was forthright, colloquial and rhythmic; she was a gifted and completely original stylist. She got people thinking about movies in new ways and inevitably she exerted a powerful influence on the generation of critics that followed her, those who (like myself) were in high school or college when we, too, first encountered Bonnie and Clyde and McCabe and Mrs. Miller and The Godfather. That influence stirred up controversy, one of several in Kael’s career. God knows she infuriated people. Unsurprisingly, directors and producers who felt slapped down in some of her reviews disliked her, and studio publicists would punish her for bad notices by cutting her from screenings. But though she had devoted fans both inside and outside the business, the passion of her conviction, the confidence with which she rendered her opinions and the strength of her arguments often unsettled her readers, especially when the movies she targeted were the ones they loved. I don’t know whether Kael was the first movie critic to discover how venomous moviegoers can become when confronted with carefully worked-through arguments against a beloved film, but some of her judgments elicited violent, menacing letters. And she had her enemies among her fellow critics – like Andrew Sarris, long associated with The Village Voice, whom she incited when, in one of her earliest (pre-New Yorker) pieces, she attacked his auteurist approach to writing about movies; Renata Adler, a peripatetic reviewer who used the publication of one of Kael’s collections, When the Lights Go Down, in 1980 to launch a lengthy and hysterical attack on her writing in The New York Review of Books; Stuart Byron, also at theVoice, who, inflating flimsy evidence, branded her a homophobe.

I knew Kael well for the last seventeen years of her life. My hero among movie critics during my college years, she became a mentor and then a close friend. Reading Kellow’s book (he interviewed me for it) and thinking about reviewing it have been, I confess, odd experiences. Anyone who knew Kael, in a sense, knows too much to read a biography of her with the calm that arises from emotional distance. But my feelings about her work didn’t alter when we became friends. She knocked me out when I read her on Barbra Streisand’s performance in Funny Girl in my first semester at college in 1968; she knocked me out again when, at the end of my third year as a college professor, I read her review of Brian De Palma’s Vietnam picture Casualties of War. And this isn’t the first time I’ve written about her: I published an essay on her work called “Critical Fervor” in The Threepenny Review a year after she retired from The New Yorker, and The Boston Phoenix ran my obituary on her in September 2001. The dual publication of Kellow’s book and the Library of America volume has rekindled some of the old controversies and has brought out of the woodwork a variety of people who – like many when she was alive, and some after her death – have evidently been champing at the bit to get in a few potshots. Frank Rich, for example, writing in The New York Times Book Review, claims to have been an admirer yet manages to re-imagine Kellow’s scrupulously fair-minded account of her post-Hollywood years at The New Yorker as retribution for her many sins (he includes the notoriously mean-spirited Adler piece in this accounting, introducing it with the phrase “Someone had to cry foul,” as if Adler were the voice of justice speaking out at last). He even accuses Kael of hypocrisy because, having mocked Dwight Macdonald for comparing Alain Resnais’s art-house darling Hiroshima, Mon Amour to Joyce and Stravinsky, she evokes Ulysses and Stravinsky’s Le sacre du printemps in her reviews of, respectively, Robert Altman’s Nashville and Bernardo Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris. It seems pretty clear that Kael’s complaint about Macdonald’s praise of the Resnais picture was that it didn’t deserve the comparison, not that it is intellectually reprehensible to allude to Joyce in a discussion about a movie.

A Life in the Dark is a conscientious piece of work. Kellow is an excellent writer and evidently a tireless researcher. The first hundred pages uncovers a vivid story about Kael’s northern-California upbringing (to Polish-Jewish émigrés who settled in a Petaluma chicken-farming community and then, when Isaac Kael lost his money in the late twenties, in San Francisco), her life among bohemians in both the Bay Area and New York in the 1940s, her scrambling among a wide range of jobs in the late forties and the fifties to support herself and her daughter (whose father, the documentary filmmaker James Broughton, threw Kael out when she told him she was pregnant), and her days managing the Berkeley Guild, a revival house, and reading her movie reviews gratis on the KPFA radio station in San Francisco. The letters he quotes reveal her spiky, jocular, anti-conventional personality, already apparently fully formed in her twenties, and occasionally an observation that prefigures her focus on disparate elements and moments in all sorts of movies once she began writing about them. In a 1941 letter to her friend Violet Rosenberg, she urges her to see So Ends Our Night for “the most beautiful shot of Frances Dee, standing in a European marketplace.”

|

| Director Sam Peckinpah |

Kellow’s misreading gets in the way when he tries to psychoanalyze Kael through her reviews – a temptation that probably no biographer of a writer could resist, but perhaps particularly misguided in this case, since Kael was so nakedly autobiographical in her writing. (It’s unlikely that anyone who confesses that she saw Vittorio De Sica’s devastating Shoeshine after a terrible, unresolvable quarrel with her boyfriend needs to have her judgments examined for hidden motives.) A glaring instance is his discussion of her review of Claude Lanzmann’s 1985 Holocaust documentary Shoah, a movie almost everyone else praised to the skies and Kael hated. (Though she had legendary fights with Shawn over her copy, it was the only time she submitted a review that he refused at first to publish at all.) Kellow pointedly prefaces this section with a paragraph on her “unsentimental attitude toward her Jewish background” and a story about her balking at a dinner party when another Jewish guest refused to eat ham and ends it with the statement, “[I]t was difficult to shake off the feeling that her thinking was influenced by other factors, of which she was only partly conscious.” But he takes the sentence that provokes this response – “If you were to set [Lanzmann] loose, he could probably find anti-Semitism anywhere” – out of context. “It was a stunning lapse of judgment,” Kellow writes, “considering that Lanzmann was looking for anti-Semitism in the most obvious of places – the death camps.” Well, no: Kael is referring not to the Nazis but to his indictment of the Polish Gentiles whom he persists in depicting as callous to the fates of the Jews thrown in the death vans. I haven’t seen the film since its release (I wrote one of the few other dissenting reviews of it), but I remember that the movie clearly conveyed Lanzmann’s anger at Polish peasants who gestured at Jews on the vans by drawing their hands across their throats. He’s sure those gestures must have been mocking; given the evidence I think it’s just as likely they were trying to warn the victims. (A friend who is fluent in Polish told me after seeing the film that Lanzmann mistranslates some of the testimony of the Poles he interviews to make them sound more insensitive.)

|

| Peter Lorre in Mad Love (1935) |

Kellow handles some of the controversies in Kael’s career more with a surer hand than others – I think he’s particularly good in both explicating and diffusing the charge that she was a homophobe. At other times, though, the emphasis his text places on the testimony of some of his interviewees and the absence of a strong counterargument allow their point of view to stand, even when it’s suspect. The book is dotted with comments by detractors who claim that once Kael took exception to a director he was dead meat as far as she was concerned, that she always put forward her pet directors, that she often overrated them, and that ironically her favoritism was just as blind as the devotion of the auteurists totheir chosen directors. But Kael’s objection to the auteur theory was that it elevated mediocre work by praising it for illuminating elements of a director’s style and for reflexively conferring greatness on any picture, no matter how drab, that carried a credit to one of certain directors. She never denied that some directors – Griffith, Renoir, De Sica, Satyajit Ray, Godard – were masters, and she never genuflected before a movie just because she’d loved the director’s previous work. She adored Altman’s work but she hated every movie he turned out between Nashville in 1975 and Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean in 1982. She adored Peckinpah’s work but not Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid or The Getaway, De Palma’s but not Obsession, Scarface, Body Double or The Bonfire of the Vanities.

Generalizations simply don’t work on Kael, because one of her great qualities as a critic was that she weighed every movie on its own merits and could see it in all its aspects – a virtue that links her to James Agee, the signal movie critic of the forties, whom she much admired. So when Kellow argues that she thought moviemakers did their best work when they were young and energetic, you think, Well, except for John Huston, Kon Ichikawa and Luis Buñuel, and how about De Sica’s return to greatness with The Garden of the Finzi-Continis? And when he puts forward the theory that she had a Magellan complex, that she found it easier to get behind filmmakers she’d discovered, you think, Well, except for Renoir and Preston Sturges and the German Expressionists. She was notoriously – and to many, not just publicists, exasperatingly – unpredictable because she didn’t believe the movies themselves could be predicted. So while she was unkind to David Lean’s epics, she loved several of his early, smaller pictures (Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, Hobson’s Choice) and she shocked everyone by giving his last, A Passage to India, a rave. She bemoaned the big studios’ chasing after the success of The Sound of Music (a picture she loathed) by turning out musical behemoths in the late sixties, but she sometimes found things to praise in them – the early scenes in Coppola’s Finian’s Rainbow, the performances in Goodbye, Mr. Chips – and she always acknowledged the times when old-style Hollywood filmmaking worked, as it did in Fiddler on the Roof. She found all of Ingmar Bergman’s work between the late fifties and the late sixties tiresome and overrated but she wrote rapturously about his apocalyptic war film Shame in 1968. She could excoriate a movie but find something marvelous hiding in one of its corners – Anthony Perkins’s performance in Play It as It Lays or Austin Pendleteon’s in Billy Wilder’s vulgarized remake of The Front Page.

|

| A scene from Shoeshine (1946) |

This disturbing hint comes at the end of a chapter, which gives it considerable weight, even though it seems to come out of the blue and Kellow never says what sort of homework might have confirmed Brown’s accusation. Did he do it himself and then decide not to share it with us? The previous chapter ends with a quote from Owen Gleiberman, who has been for many years the film critic at Entertainment Weekly, in which he claims that while he was friendly with Kael he applied for admission to the National Society of Film Critics and was initially turned down. When he asked her to tell him why, she gave him an answer that he knew immediately wasn’t the truth so he decided to break with her because “I realized that she would lie to her critic acolytes in order to keep them in line.” But nothing in the story suggests how lying to Gleiberman would keep him in line; the story is melodramatic and implausible and seems to promote his presentation of himself as intuitive and perceptive. You’d think Kellow would be smart enough not to quote this sort of nonsense, at least not without some editorial commentary. Instead he adds, “Gleiberman always considered himself the truest of all the Paulettes because he had realized that he had to be himself. ‘To be true to what Pauline taught us,’ he said, ‘you had to break with her.’ ” Gleiberman paints himself as a hero, a man of singular integrity, and by giving him the final word on the subject and refusing to challenge it Kellow lets this self-promotion stand.

Perhaps it’s unfair to expect Kellow to do for Kael’s writing what, say, Sanford Schwartz does in his fine introduction to The Age of Movies, because Schwartz isn’t a biographer and Kellow isn’t a critic. But how do you write the life of a movie critic if you don’t have much to offer on the subject of movies? I realize that it’s unfair to single out all the problems I had with A Life in the Dark and discuss them at such length because it gives the book’s considerable virtues short shrift. But the lacunae in Kellow’s book seem to me to be precisely in the areas where Kael’s accomplishments are always underappreciated and where the traditional complaints against her need to be placed in a context that he doesn’t seem equipped to provide. The book is fair, if weighing everyone’s opinion is fair, but it isn’t always accurate. Schwartz argues that Kael’s body of work “sometimes has the impact of a single long, indirect, and utterly original kind of autobiography” and I suppose that, in the end, that’s the biography of Pauline Kael that I prefer.

- originally published on November 17, 2011 in Critics at Large.

– Steve Vineberg is Distinguished Professor of the Arts and Humanities at College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, where he teaches theatre and film. He also writes for The Threepenny Review, The Boston Phoenix and The Christian Century and is the author of three books: Method Actors: Three Generations of an American Acting Style; No Surprises, Please: Movies in the Reagan Decade; and High Comedy in American Movies.

– Steve Vineberg is Distinguished Professor of the Arts and Humanities at College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, where he teaches theatre and film. He also writes for The Threepenny Review, The Boston Phoenix and The Christian Century and is the author of three books: Method Actors: Three Generations of an American Acting Style; No Surprises, Please: Movies in the Reagan Decade; and High Comedy in American Movies.

Talking Out of Turn #4: Pauline Kael (1983)

From 1981 to 1989, I was assistant producer and co-host of the radio show, On the Arts, at CJRT-FM in Toronto. With the late Tom Fulton, who was the show's prime host and producer, we did a half-hour interview program where we talked to artists from all fields. In 1994, after I had gone to CBC, I had an idea to collate an interview anthology from some of the more interesting discussions I'd had with guests from that period. Since they all took place during the eighties, I thought I could edit the collection into an oral history of the decade from some of its most outspoken participants. The book was assembled from interview transcripts and organized thematically. I titled it Talking Out of Turn: Revisiting the '80s. With financial help from the Canada Council, I shaped the individual pieces into a number of pertinent themes relevant to the decade. By the time I began to contact publishers, though, the industry was starting to change. At one time, editorial controlled marketing. Now the reverse was now starting to take place. Acquisition editors, who once responded to an interesting idea for a book, were soon following marketing divisions concerned with whether the person doing it was hot enough to sell it.

For a few years, I flogged the proposal to various publishers but many were worried that there were too many people from different backgrounds (i.e. Margaret Atwood sitting alongside Oliver Stone). Another publisher curiously chose to reject it because, to them, it appeared to be a book about me promoting my interviews (as if I was trying to be a low-rent Larry King) rather than seeing it as a commentary on the decade through the eyes of the guests. All told, the book soon faded away and I turned to other projects. However, when recently uncovering the original proposal and sample interviews, I felt that maybe some of them could find a new life on Critics at Large.

Talking Out of Turn had one section devoted to critics who ran against the current of popular thinking in the eighties. That chapter included discussions with film critic Vito Russo (The Celluloid Closet) who wrote a book about gay cinema before the horror of AIDS changed the landscape; also Jay Scott, who would later die from AIDS, spoke about how, despite being one of Canada's sharpest and wittiest writers on movies, he was initially a reluctant critic; and author Margaret Atwood who turned to literary criticism in her 1986 book Second Words. She discussed -- from an author's perspective -- the value of criticism and how it was changing for the worst during this decade.

There was also a discussion with New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael who two years earlier had returned to writing after a brief hiatus as a consultant in Hollywood. Kael's career began at a fortuitous time in movie history during the sixties when Godard, Truffaut, Bertolucci and Arthur Penn dramatically changed the face of the art form. Her reviews also changed the intent and style of criticism. She fought the auteur school of Andrew Sarris that was worshipful of film directors. She created instead an intuitive and personal approach to criticism based on examining her responses to the work and illuminating that experience in the context of art, politics, popular culture and literature. In a sense, she acted on D.H. Lawrence's sharp observation in his Classic Studies in American Literature: "Never trust the artist, trust the tale."

When we met to talk at the Windsor Arms hotel in Toronto, during her book tour for her compendium, 5001 Nights at the Movies, the Reagan decade was already beginning to have its deadening impact on the movie industry. I had only been reviewing professionally for about three years and was already beginning to witness a decline in quality pictures as well as the decline of a critical and discerning audience. With that question rattling in my brain, we began the interview.

kc: You once wrote in the seventies, a great decade for movies, that the hardest job for a critic to do is to convince a movie audience that certain visceral entertainment like The Towering Inferno and Death Wish were not good films, but crudely manipulative ones instead -- Is it becoming even more difficult to be that convincing today?

pk: Oh yes. I think it's still true that if people are emotionally moved by a movie they think it is a great movie. They can't believe that those emotions were pulled out by very simple tricks. It's funny...if you reduce it to its simplest and let's say you see a boy, and the boy loses his dog, and the dog gets run over, of course, it's going to make you cry. Well, there are certain kinds of romantic stories that will have the same effect. I'd say there is a terrific example in An Officer and a Gentleman. I've gotten very hostile mail from people who thought that it was so realistic and true to the life of poor people. They couldn't understand why I took that side of it with a grain of salt.

kc: I responded similarly with On Golden Pond.

pk: (laughing) I responded negatively all the way! That film exploited the public's knowledge that Henry Fonda was dying and the material itself was such obvious phoniness. It's such a prettied-up view of old age with the man and the wife so supportive and loving. Have you ever known an old couple even remotely like this? There were none of the hostilities coming out that would have developed in that marriage over the years. It didn't even come out in relation to their daughter. You know, if the father had mistreated the daughter all those years and made her miserable, and if the mother loved her, surely this would have been a bone of contention between the parents. And if you're the daughter and you've had this rejecting stink of a father, I don't know if you're going to come out in the end and say, "I love you."

kc:...or do back-flips in the pond to get your father's approval.

pk: I mean, if you have to do back-flips in order to be accepted by a parent, I think it's hopeless anyway.

kc: I wonder if this change in both movies and the audience follows up on that piece you wrote in The New Yorker in the late seventies called "Fear of Movies." In this piece, you stated that audiences were becoming afraid of exciting movies, or violent ones, because of what it stirred up in them. Audiences, according to your piece, were starting to embrace more banal, or safe pictures. This revelation touched a nerve in me because there were some pretty interesting pictures that I couldn't get certain friends to see because they'd say, "I don't need that." How pervasive is this attitude today?

pk: I've been jumped on and attacked for that article more than anything I've ever written. Now I'm being accused of being...oh...pro-violence, or pro-blood and guts. People completely misread what I was trying to say. I think a lot of people want to misread anything on the subject of violence because they don't want to deal with it analytically. They want to reject all violence instead of realizing that it's a basic part of all dramatic, literary and film art. It's as if, once people reject the really bloody revenge fantasies, or the street western movie, or even the horror movie, they transfer it also to movies that upset them, or really get them excited. They think that film art is a polite foreign film like Truffaut's The Woman Next Door which is like a situation comedy being treated very seriously. A lot of mediocre fillms from Europe are getting great press and marvellous response in North America because they're safe. They don't have the kind of churning emotion that you get in The Godfather, Mean Streets, or Taxi Driver.

kc: Why do you think we are getting this kind of timidness now?

pk: I think it's partly because our whole society seems so violent and fraught with danger. In the United States, we still have a lot of unresolved racial problems in the cities. Put simply: People want safety at the movies. They don't want anything that reminds them of the horror on the streets.

kc: But if some movies have the ability to get us to confront our fears, why would we choose to reject them?

pk: I think many people feel that they're rejecting them for their own peace of mind. And you can't convince them otherwise. If you say it's a great movie and it intensifies your experiences without in any way exploiting violence -- in fact, it makes you hate the violent characters -- people still want to remove that entire experience. Many people thought The Godfather was a violent movie and didn't want to think of it as a piece of film art. It was easier to make fun of it as a cheap gangster movie than admit that it did excite them.

kc: This reminds me of another film from a couple of years back that also inspired strong negative reaction and that was Brian de Palma's Dressed to Kill. At the screening I attended, feminist groups were outside encouraging people to walk out because they felt the movie was celebrating violence against women.

pk: They did that in the States as well. I thought that was a very naive reading of the movie because the Angie Dickinson character (ed. a housewife who is murdered by a psychopath in an elevator after having had sexual relations with a man who she just met) is darling. You feel so sorry for her. Here is this sweet woman who isn't harming anyone and this hideous irony happens where she steps out and tries to have some sexual pleasure and she gets killed after it. It's so subtly funny in the way that it's handled. Somehow the feminist critics have treated it as if she's being punished for her sexual transgression. I don't think that's remotely what's going on in the movie.

kc: Why then do you think political groups would get so incensed about Dressed to Kill if it doesn't eroticize the murder of women?

pk: I think that there often is a misreading of a movie in terms of issues. Certain people, when they are organizing, homosexual and feminist groups, almost wilfully misread what is going on in a movie in order to feel that they are being insulted. Some black pressure groups have been this way about the portrayal of blacks on the screen. Now producers are afraid to have any black characters who aren't the greatest thing you've ever seen because people will get upset. It's unfortunate. I've been criticized by certain feminist groups for not calling for legal censorship which I happen to think it the last thing that movies need. The point is, they are so upset over the violence issue that I don't think they look at how violence functions within the movie. They just decide that any acts of violence against women have to be protested against.

kc: But there are some movies that have exploited violence against women, don't you think?

pk: Sure. There are also movies that gloat about the killing of men, too. Often those films aren't the ones that are protested. It's generally the best work -- the work that really doesn't do that, the kind that involves people emotionally. After all, why was it D.H. Lawrence who got people so upset that they wanted to censor him? They don't censor somebody who doesn't make them feel anything. I think it's because Brian de Palma does get at very basic emotions, as well as some rather subtle intellectual concepts, that they're offended by him. On the other hand, something like...oh...that Hitchcock film from the sixties where that woman is strangled....

kc: Frenzy?

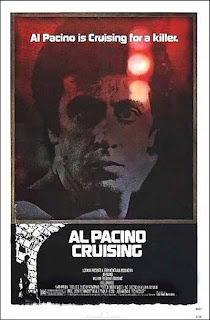

pk: Yes. Frenzy. It's amazing. I found that film rather offensive because the woman is made to look ridiculous right at the point where she was being killed. I thought there was something very ugly -- spiritually -- about that. It's very odd that no one protested that. I've seen Clint Eastwood movies, and I'm thinking of [Magnum Force] where a black whore is made to swallow Drano. There was nothing in the scene to excite the audience except the brutality. It's generally the hacks that do that and nobody protests them. I think the movie Cruising was probably mangled by the protests because I think the movie-makers weakened the idea. The book that the movie is based on has a terrific subject for a movie. There is a legitimate idea there that a man who is that interested in hunting a killer of homosexuals becomes a killer of homosexuals. Even though it was an ugly book to read, there was some psychological validity to it. By the time they made the movie inoffensive to homosexual pressure groups, they had nothing left.

kc: This brings me back to what we were discussing around the fear of movies.You wrote another piece earlier in the seventies about the audience watching Arthur Penn's Alice Restaurant as an audience that was trying to feel its way through that movie. From what we've been talking about, audiences today don't seem that willing to take a chance on a film that doesn't spell it all out.

pk: It's true. People today are more closed off. I think in the seventies they were more open to movies, as they were also in the sixties. It's harder now to get them to go out and see something a little unusual. I even think they resent it when they have to sit back and feel their way in. I don't think they want to anymore. Who knows if it's the influence of television, or the Reagan era, or what it is? They just seem hostile if it isn't a movie that just lays everything on the line like On Golden Pond. That's the kind of movie that makes me resentful because I feel like I'm being treated like an idiot. Unfortunately, quite a few people want movies to be as simple as TV.

- originally published on November 26, 2010 in Critics at Large.

— Kevin Courrier is a writer/broadcaster, film critic, teacher and author. His forthcoming book is Reflections in the Hall of Mirrors: American Movies and the Politics of Idealism.

For a few years, I flogged the proposal to various publishers but many were worried that there were too many people from different backgrounds (i.e. Margaret Atwood sitting alongside Oliver Stone). Another publisher curiously chose to reject it because, to them, it appeared to be a book about me promoting my interviews (as if I was trying to be a low-rent Larry King) rather than seeing it as a commentary on the decade through the eyes of the guests. All told, the book soon faded away and I turned to other projects. However, when recently uncovering the original proposal and sample interviews, I felt that maybe some of them could find a new life on Critics at Large.

Talking Out of Turn had one section devoted to critics who ran against the current of popular thinking in the eighties. That chapter included discussions with film critic Vito Russo (The Celluloid Closet) who wrote a book about gay cinema before the horror of AIDS changed the landscape; also Jay Scott, who would later die from AIDS, spoke about how, despite being one of Canada's sharpest and wittiest writers on movies, he was initially a reluctant critic; and author Margaret Atwood who turned to literary criticism in her 1986 book Second Words. She discussed -- from an author's perspective -- the value of criticism and how it was changing for the worst during this decade.

|

| Pauline Kael |

When we met to talk at the Windsor Arms hotel in Toronto, during her book tour for her compendium, 5001 Nights at the Movies, the Reagan decade was already beginning to have its deadening impact on the movie industry. I had only been reviewing professionally for about three years and was already beginning to witness a decline in quality pictures as well as the decline of a critical and discerning audience. With that question rattling in my brain, we began the interview.

kc: You once wrote in the seventies, a great decade for movies, that the hardest job for a critic to do is to convince a movie audience that certain visceral entertainment like The Towering Inferno and Death Wish were not good films, but crudely manipulative ones instead -- Is it becoming even more difficult to be that convincing today?

pk: Oh yes. I think it's still true that if people are emotionally moved by a movie they think it is a great movie. They can't believe that those emotions were pulled out by very simple tricks. It's funny...if you reduce it to its simplest and let's say you see a boy, and the boy loses his dog, and the dog gets run over, of course, it's going to make you cry. Well, there are certain kinds of romantic stories that will have the same effect. I'd say there is a terrific example in An Officer and a Gentleman. I've gotten very hostile mail from people who thought that it was so realistic and true to the life of poor people. They couldn't understand why I took that side of it with a grain of salt.

kc: I responded similarly with On Golden Pond.

pk: (laughing) I responded negatively all the way! That film exploited the public's knowledge that Henry Fonda was dying and the material itself was such obvious phoniness. It's such a prettied-up view of old age with the man and the wife so supportive and loving. Have you ever known an old couple even remotely like this? There were none of the hostilities coming out that would have developed in that marriage over the years. It didn't even come out in relation to their daughter. You know, if the father had mistreated the daughter all those years and made her miserable, and if the mother loved her, surely this would have been a bone of contention between the parents. And if you're the daughter and you've had this rejecting stink of a father, I don't know if you're going to come out in the end and say, "I love you."

|

| Henry Fonda and Katherine Hepburn in On Golden Pond |

pk: I mean, if you have to do back-flips in order to be accepted by a parent, I think it's hopeless anyway.

kc: I wonder if this change in both movies and the audience follows up on that piece you wrote in The New Yorker in the late seventies called "Fear of Movies." In this piece, you stated that audiences were becoming afraid of exciting movies, or violent ones, because of what it stirred up in them. Audiences, according to your piece, were starting to embrace more banal, or safe pictures. This revelation touched a nerve in me because there were some pretty interesting pictures that I couldn't get certain friends to see because they'd say, "I don't need that." How pervasive is this attitude today?

pk: I've been jumped on and attacked for that article more than anything I've ever written. Now I'm being accused of being...oh...pro-violence, or pro-blood and guts. People completely misread what I was trying to say. I think a lot of people want to misread anything on the subject of violence because they don't want to deal with it analytically. They want to reject all violence instead of realizing that it's a basic part of all dramatic, literary and film art. It's as if, once people reject the really bloody revenge fantasies, or the street western movie, or even the horror movie, they transfer it also to movies that upset them, or really get them excited. They think that film art is a polite foreign film like Truffaut's The Woman Next Door which is like a situation comedy being treated very seriously. A lot of mediocre fillms from Europe are getting great press and marvellous response in North America because they're safe. They don't have the kind of churning emotion that you get in The Godfather, Mean Streets, or Taxi Driver.

kc: Why do you think we are getting this kind of timidness now?

pk: I think it's partly because our whole society seems so violent and fraught with danger. In the United States, we still have a lot of unresolved racial problems in the cities. Put simply: People want safety at the movies. They don't want anything that reminds them of the horror on the streets.

kc: But if some movies have the ability to get us to confront our fears, why would we choose to reject them?

|

| Al Pacino and Marlon Brando |

kc: This reminds me of another film from a couple of years back that also inspired strong negative reaction and that was Brian de Palma's Dressed to Kill. At the screening I attended, feminist groups were outside encouraging people to walk out because they felt the movie was celebrating violence against women.

pk: They did that in the States as well. I thought that was a very naive reading of the movie because the Angie Dickinson character (ed. a housewife who is murdered by a psychopath in an elevator after having had sexual relations with a man who she just met) is darling. You feel so sorry for her. Here is this sweet woman who isn't harming anyone and this hideous irony happens where she steps out and tries to have some sexual pleasure and she gets killed after it. It's so subtly funny in the way that it's handled. Somehow the feminist critics have treated it as if she's being punished for her sexual transgression. I don't think that's remotely what's going on in the movie.

|

| Angie Dickinson in Dressed to Kill |

pk: I think that there often is a misreading of a movie in terms of issues. Certain people, when they are organizing, homosexual and feminist groups, almost wilfully misread what is going on in a movie in order to feel that they are being insulted. Some black pressure groups have been this way about the portrayal of blacks on the screen. Now producers are afraid to have any black characters who aren't the greatest thing you've ever seen because people will get upset. It's unfortunate. I've been criticized by certain feminist groups for not calling for legal censorship which I happen to think it the last thing that movies need. The point is, they are so upset over the violence issue that I don't think they look at how violence functions within the movie. They just decide that any acts of violence against women have to be protested against.

kc: But there are some movies that have exploited violence against women, don't you think?

pk: Sure. There are also movies that gloat about the killing of men, too. Often those films aren't the ones that are protested. It's generally the best work -- the work that really doesn't do that, the kind that involves people emotionally. After all, why was it D.H. Lawrence who got people so upset that they wanted to censor him? They don't censor somebody who doesn't make them feel anything. I think it's because Brian de Palma does get at very basic emotions, as well as some rather subtle intellectual concepts, that they're offended by him. On the other hand, something like...oh...that Hitchcock film from the sixties where that woman is strangled....

|

| Barbara Leigh-Hunt in Frenzy |

pk: Yes. Frenzy. It's amazing. I found that film rather offensive because the woman is made to look ridiculous right at the point where she was being killed. I thought there was something very ugly -- spiritually -- about that. It's very odd that no one protested that. I've seen Clint Eastwood movies, and I'm thinking of [Magnum Force] where a black whore is made to swallow Drano. There was nothing in the scene to excite the audience except the brutality. It's generally the hacks that do that and nobody protests them. I think the movie Cruising was probably mangled by the protests because I think the movie-makers weakened the idea. The book that the movie is based on has a terrific subject for a movie. There is a legitimate idea there that a man who is that interested in hunting a killer of homosexuals becomes a killer of homosexuals. Even though it was an ugly book to read, there was some psychological validity to it. By the time they made the movie inoffensive to homosexual pressure groups, they had nothing left.

kc: This brings me back to what we were discussing around the fear of movies.You wrote another piece earlier in the seventies about the audience watching Arthur Penn's Alice Restaurant as an audience that was trying to feel its way through that movie. From what we've been talking about, audiences today don't seem that willing to take a chance on a film that doesn't spell it all out.

pk: It's true. People today are more closed off. I think in the seventies they were more open to movies, as they were also in the sixties. It's harder now to get them to go out and see something a little unusual. I even think they resent it when they have to sit back and feel their way in. I don't think they want to anymore. Who knows if it's the influence of television, or the Reagan era, or what it is? They just seem hostile if it isn't a movie that just lays everything on the line like On Golden Pond. That's the kind of movie that makes me resentful because I feel like I'm being treated like an idiot. Unfortunately, quite a few people want movies to be as simple as TV.

- originally published on November 26, 2010 in Critics at Large.

— Kevin Courrier is a writer/broadcaster, film critic, teacher and author. His forthcoming book is Reflections in the Hall of Mirrors: American Movies and the Politics of Idealism.

No comments:

Post a Comment